Opioids in the Workplace: Warning signs and how to respond to a poisoning

February 14, 2024

By

Todd Humber

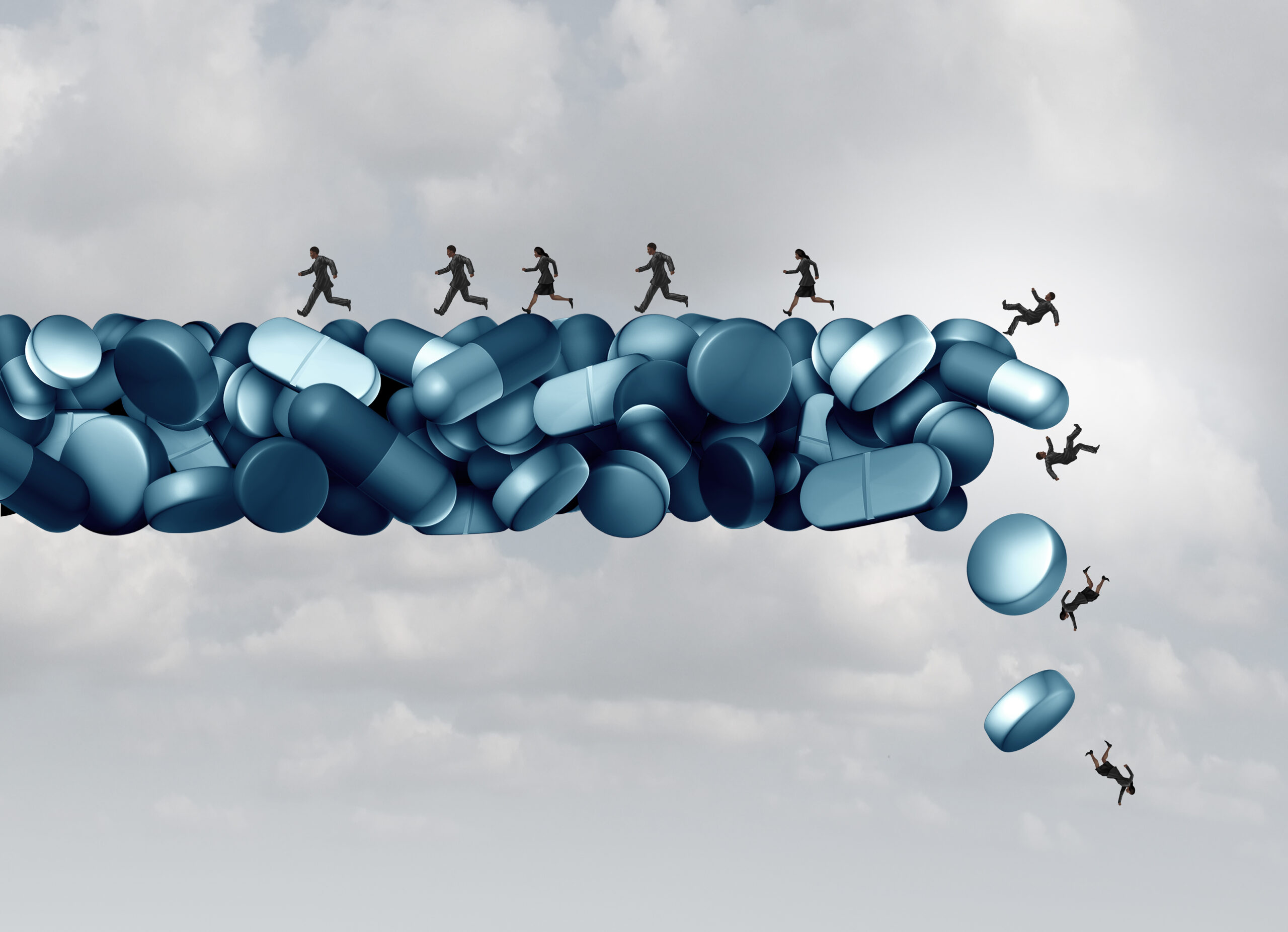

Photo: Getty Images

There is no sure-fire way to spot someone who is at risk of an opioid poisoning or substance abuse, but there are some red flags to watch out for, according to Vicky Waldron, Vancouver-based executive director of the Construction Industry Rehabilitation Plan.

“What you’re looking for is someone that’s behaving out of the norm,” she said, noting the warning signs can vary not just by individual but also by gender.

Such deviations might include increased irritability, argumentativeness, and risk-taking behaviors, particularly in men who may express stress through outward anger and aggression.

“It usually starts with kicking of tools or throwing things around,” said Waldron. “And this is something that’s going on for a while that might be getting progressively worse.”

Vicky Waldron, executive director,

Construction Industry Rehabilitation Plan.

For women, the signs might manifest as withdrawal, becoming more tearful, or neglecting personal hygiene, she said. Waldron made the comments as part of a roundtable discussion at the Opioids in the Workplace virtual event. Presented by OHS Canada and Talent Canada on Jan. 31, it attracted nearly 350 professionals from across the country.

A ‘perfect storm’ in construction

Stats and research have shown that workers in construction are at higher risk of opioid poisonings, and there are a few things driving that, according to Waldron. First is the transient nature of the industry.

Layered on top of that is the toxicity of the drugs and a push to get injured workers back on the job quickly because of labour shortages, she said.

“There is a pressure to get back to work quickly,” said Waldron.

Warning signs by age

Julian Toy, a substance abuse professional and a former addict, said it’s important to also consider the age of the worker. It’s not that unusual for a 19-year-old, for example, to think it’s cool to go out and get drunk and high on the weekends, he said.

“That’s normal, for people who are young, to experiment with substances,” said Toy.

Julian Toy, H.S.C., Substance Abuse Professional

But if you’re looking at a 40-year-old worker exhibiting the same behaviour, “that’s something I would take a closer look — at that employee’s attendance, performance, and behaviour simply because of the fact that’s not age appropriate.”

He agreed with the warning signs raised by Waldron, and noted that there is often no transition period between “anger and happiness, despair and joy” among an addict.

“It will happen instantly, it’s not going to happen slowly,” said Toy. “A person can go from despondent to angry within seconds, with no noticeable explanation. If a person has substance abuse disorder, you’d probably be left confused at the wide swing of emotions.”

What to do if you spot a warning sign

Ken Brodie, senior HSE specialist for Modern Niagara Vancouver, said construction sites are inherently dangerous workplaces — even for clear-minded individuals. An impaired worker, either through medication, alcohol, or drugs, can pose a significant risk.

If someone on his team suspects a worker is under the influence, they intervene, he said.

“We have a talk with that person, and we take them somewhere private,” said Brodie. “And we have two people do this so it’s unbiased.”

The first question asked is: “What’s going on?”

“Hopefully, we can get them talking and they’ll probably self-disclose, because that’s what we found in the past,” said Brodie. “They’ll actually tell you what’s going on. Maybe it was a medical emergency — the medications were changed. Maybe there’s a family emergency, something happened — marital discord.”

Ken Brodie, Senior HSE Specialist, Modern Niagara Vancouver.

Be proactive so you can be reactive

Brodie said that, in order to be reactive to an opioid situation, a company has to be proactive in developing policies — and that includes training and communication.

“There’s no more helpless feeling than when a person is confronted with an emergency situation and they don’t know what to do to help,” he said. “Our employees are excellent at building… and making buildings work. But they’re not trained medical personnel.”

But giving staff basic information can give them a leg up when they’re confronted with an overdose, he said. That includes a policy that outlines guidelines and responsibilities, he said.

“We constantly offer free Naloxone training courses,” he said, adding that they also pay the worker for the time they’re in the training.

He noted that, in the past, workers would have to use needles — but the new nasal sprays are handy and simple to use. “It’s not daunting at all… one spray up the nostril.”

One-quarter (25 per cent) of Modern Niagara Vancouver employees have been trained on using Naloxone, he said — from apprentices right up to the CEO.

SAVE ME: Responding to an overdose

The first thing to do in the event of an overdose is to call 911, said Waldron. Then it’s time to follow the rest of the “SAVE ME” steps, republished here from the Government of British Columba’s website:

- S – Stimulate. Check if the person is responsive, can you wake them up? If they are unresponsive, call 911. The sooner you call, the better the chance of recovery.

- A – Airway. Make sure there is nothing in the mouth blocking the airway, or stopping the person from breathing. Remove anything that is blocking the airway.

- V – Ventilate. Help them breathe. Plug the nose, tilt the head back and give one breath every 5 seconds.

- E – Evaluate. Do you see any improvement? Are they breathing on their own? If not, prepare naloxone.

- M- Medication. Administer the Naloxone.

- E – Evaluate and support. Is the person breathing? Naloxone usually takes effect in 3-5 minutes. If the person is not awake in 5 minutes, give one more dose.

The reason Naloxone isn’t administered immediately is that it puts people into “precipitated withdrawal,” said Waldron.

“It’s a harsh, fast, and quick withdrawal,” she said. “And so people bolt upright. It will put them into that withdrawal, and they may get up, run away, and they may go off and use again straight away, because it’s incredibly painful.”

If you haven’t called 911 by that point, there is a danger that they will take opioids again — and they won’t get the effect of them.

“Because they’ve got Naloxone in their system as that dissipates,” she said, noting that it has a half life of about 90 minutes while opioids have a half life of between four and eight hours.

“What that means is that once the Naloxone has disappeared, all the opioids that were in the system are now going to reattach to the receptor sites, they go back into the brain — plus the new amount of opioids they’ve used,” she said. “That can really lead to an increased risk of fatalities.”

Brodie also offered another useful tip — which is to send someone to the entrance of the worksite to greet and guide the first responders.

“It’s daunting — construction sites — even for the workers, but for somebody new to the site? Send somebody out to find them,” he said.

Workplace factors linked to opioid use

The panel also spent some time discussing some of the workplace factors that are linked to opioid use.

Gina Vahlas, secretary, College for the Certification of Canadian Professional Ergonomists and product owner, Prevention Business Product Management, at WorkSafeBC, said it’s important to look at the personal factors that can lead people down the path to substance abuse.

“There is a link between workplace factors and opioid abuse,” she said. It’s something she has witnessed first-hand when she worked in a physical therapy clinic.

Gina Vahlas, secretary, College for the Certification of Canadian Professional Ergonomists and product owner, Prevention Business Product Management, WorkSafeBC.

It was not uncommon to observe a recurring cycle among patients with muscular injuries or disorders, said Vahlas. Initially, these individuals would seek treatment, make a recovery, and subsequently return to their professional environments. However, the relief was often temporary.

“When they go back to full-time duties and hours, they would end up going off work again because of the pain,” she said. “Because the workplace factors that created the injury did not change.”

Physical factors are high on the list of things to consider, such as “high force, awkward postures — which are extreme body positions, like working with our arms over our head or bending forward,” she said. Other dangers include repetition, temperature, vibrations, and contact stress.

“There are other cognitive factors, such as perception and memory and psychosocial factors, such as low job control and getting rewarded or paid more for doing more — which incentivizes workers to go beyond what is healthy and safe,” said Vahlas.

She views the opioid crisis as more of a “pain crisis” than anything else. Programs that can ease pain, including ergonomics, can eliminate the need to take strong medication in the first place.

“Focusing solely on the use of opioids attacks the symptoms of the the crisis and will not solve the problem,” she said.