Cognitive health: a hidden challenge with tremendous workplace implications

By Conny Glenn, Allan Smofsky and Rensia Melles

Now, more than ever, it’s time for workplaces to recognize the importance of cognitive health in determining the success of their employees and their organization.

Technological implementation, constant connectivity and the rapid pace of change are some of the main issues affecting workers’ mental health. (Getty Images)

Workplaces often spend considerable time and effort in reviewing job performance and modifying job descriptions to meet the evolving needs of the organization.

Cognitive function is a key element of almost all jobs today; however, there is a significant deficit in our recognition, assessment and understanding of cognitive demands — across all jobs.

This can have major implications for workplaces — from basic performance issues to serious events such as accidents.

Cognitive function is a broad term that refers to mental processes involved in the acquisition of knowledge, manipulation of information, reasoning, management of emotion, and control of motor abilities.

COVID-19 has done more than create widespread awareness of the importance of public and mental health — it has opened up the discussion about these cognitive functions.

Reports of long-term COVID “brain fog” have put the spotlight on the impact of cognitive impairment on function and quality of life. There is a growing awareness that many things can impact cognition.

COVID brain fog has been measured on a large scale. A recent study published in the Lancet evaluated cognitive abilities in 81,337 people and found that those who previously had COVID-19 tended to score lower on measures of reasoning, problem solving and planning compared to people who were never infected. The authors noted that the scale of the observed deficit was “not unsubstantial.”

What is important to note from the study is that although people who had been hospitalized and put on ventilators had the greatest impairments, even those who had relatively mild COVID-19 symptoms showed some cognitive deficit, and those deficits have been noted to persist in some cases for months or remain unresolved.

This impact is not unique to COVID-19. A previous study showed similar ramifications from SARS and MERS, as well as from chronic diseases, mental illnesses, and injuries. What is truly highlighted by these studies is that cognitive function is an area of human health that we have largely ignored.

Now, more than ever, it’s time for workplaces to recognize the importance of cognitive health in determining the success of their employees and their organization.

The importance of cognitive function

Cognitive abilities are brain-based skills we need to carry out any task from the simplest to the most complex.

Cognitive skills include abilities like navigation, concentration, problem solving, managing emotions, recognizing risks and hazards, and decision making.

When a worker suffers a cognitive challenge, it can impact their ability to perform job-based tasks. For example, if a person struggles with spatial perception (the ability to navigate) this might prevent them from moving their mouse accurately on screen or driving a forklift through a warehouse.

Just like physical ability, cognitive function or ability exists on a spectrum. Workplaces have become comfortable — or at least aware — that they can and should accommodate physical and mental health challenges faced by their employees, but cognitive challenges are often inadequately considered, if at all.

There seem to be two primary misconceptions about cognitive impairment:

- That it only happens to people as they age (dementia and Alzheimer’s).

- That once you have a cognitive impairment it is permanent and very little can be done to maintain or improve cognitive function.

Fortunately, these misconceptions are just that — misconceptions.

First, anyone can suffer from cognitive challenges regardless of age. Although aging is one of the biggest risk factors for cognitive decline, dementia and Alzheimer’s are not the only causes of cognitive impairment. Poor health, physical illnesses (i.e. diabetes) and injury to the brain can result in cognitive impairment. Additionally, depression, chronic lack of sleep, and a wide range of medications can cause cognitive impairment.

Admitting that you are struggling with concentration, memory, or cognitive tasks unrelated to aging or head injury is often harder than admitting you are struggling with depression or burnout. In the United States, Americans were twice as fearful of losing their mental capacity as having diminished physical ability.

According to Neuroscience Canada, one in three individuals will experience a brain disorder during their lifetime, yet it is often treated as a side effect that will fix itself once the “core” concern is addressed.

Cognitive functional challenges affect performance of regular activities, the ability to enjoy life, and at times can even pose a safety hazard to the person or to others. Meanwhile, fear of being stigmatized, fear of loss of control or status can prevent open dialogue and seeking appropriate help.

Secondly, a variety of lifestyle and health interventions can maintain and improve cognitive health. For example, a study published by the American Academy of Neurology in February 2019 showed that higher levels of total daily activity is associated with better cognition in older adults. Similar studies support eating a healthy diet, not smoking, not drinking excessively, managing weight and stress, getting adequate sleep, and remaining mentally active as measures to improve, prevent, and slow cognitive decline.

Given the impact decreased cognitive function can have, it needs to be viewed as critically important for consideration, and not as just a secondary symptom of disease, disorder or injury. Challenges with cognitive function also need not be considered permanent, nor necessarily be equated with a loss of intelligence. There are opportunities to evaluate, treat, manage, and improve cognitive function.

Cognitive health and the workplace

As discussed, cognitive challenges can take many forms.

Unfortunately, these challenges often translate into negative impacts in the workplace and in more ways than we realize. Cognitive challenges can affect individual and team performance, risk assessment and management, workplace absenteeism and return to work planning, and overall human resource management.

Performance

All jobs require some degree of effective cognitive function, and in many cases the cognitive demands, especially today, are significant.

While “basic” cognitive skills such as concentration and short-term memory are important elements across the board, as discussed above, heightened demands on cognitive function often occur in workplaces with the implementation of technological advances, significant new projects/changes (i.e. mergers and acquisitions), new operational or administrative processes, and more.

For a time, performance levels may be less than optimal until sufficient training/learning has occurred and/or tasks have been properly assigned.

Risk assessment and management

From the safety and risk management perspective cognitive function is important in recognizing and evaluating risk to prevent injury to persons, and damage or lost opportunity to businesses. Cognitive abilities such as attention, visual and auditory processes, reasoning and judgement are all important for being able to do an accurate risk-benefit analysis.

We assess risk regularly when we cross a busy street or buy a lottery ticket. At work we do the same when we decide to climb a ladder or develop a new product. When cognition is challenged we may miss an important detail like the ladder is in a high traffic zone, or that a small but critical part of a new product has a high failure rate which may cause legal claims. In either case injury of some sort is the likely result.

Work absence and return to work

In addition to performance and safety issues while at work, cognitive challenges can impact disability management and return to work (RTW) planning and execution. Moreover, chronic diseases such as cancer, diabetes and respiratory issues, often involve mental health co-morbidities. This has been documented to result in anxiety and depression, which one study showed as being largely influenced by cognitive challenges.

Many workplace health resources and programs do not address cognitive function successfully, if at all. RTW planning for those on short or long-term disability, for example, often fail to test cognitive function, despite the degree of cognitive demands associated with most jobs an employee would be returning to.

Many readers of this commentary will be familiar with the legal requirement for an employer to accommodate an employee’s return to work.

Yet, cognitive function is often not effectively considered in the accommodation discussion, which may be one reason why return to work plans often do not work out as expected. An argument could be successfully made for adding a cognitive function assessment much earlier in the absence/disability management process — i.e. at the onset of a mental health-related disability to improve the outcome of the process.

Research from the Institute for Work & Health (IWH) shows that organizations where employees successfully return to work share these seven key principles:

- The workplace has a strong commitment to health and safety, which is demonstrated by the behaviours of everyone in the workplace.

- The employer offers modified work to ill employees so they can return as early as is feasible to work that is suitable to their temporary abilities.

- Return to work planners ensure that the return to work plan supports the returning employee without putting co-workers and supervisors at a disadvantage.

- Supervisors are trained and included in return-to-work planning.

- The employer makes early and considerate contact with ill employees.

- Someone has the responsibility to coordinate return to work.

- Employers and health-care providers exchange information with each other as needed.

We note that several of the seven principles relate to mental health/well-being, and to some extent by inference, cognitive function.

Resource gaps

Another gap in addressing cognitive challenges lies in the current array of mental health resources in the workplace arena.

Workplace mental health resources still today are focused on helping individuals to cope with and address their main stressors, but often miss the perspective of the cognitive challenges that arise from these same stressors.

For such programs and resources to be truly effective, it is important that cognitive function be considered. No matter where individuals are with regard to their ability to work, cognitive health is a vital element — and often a missing link — in organizational planning.

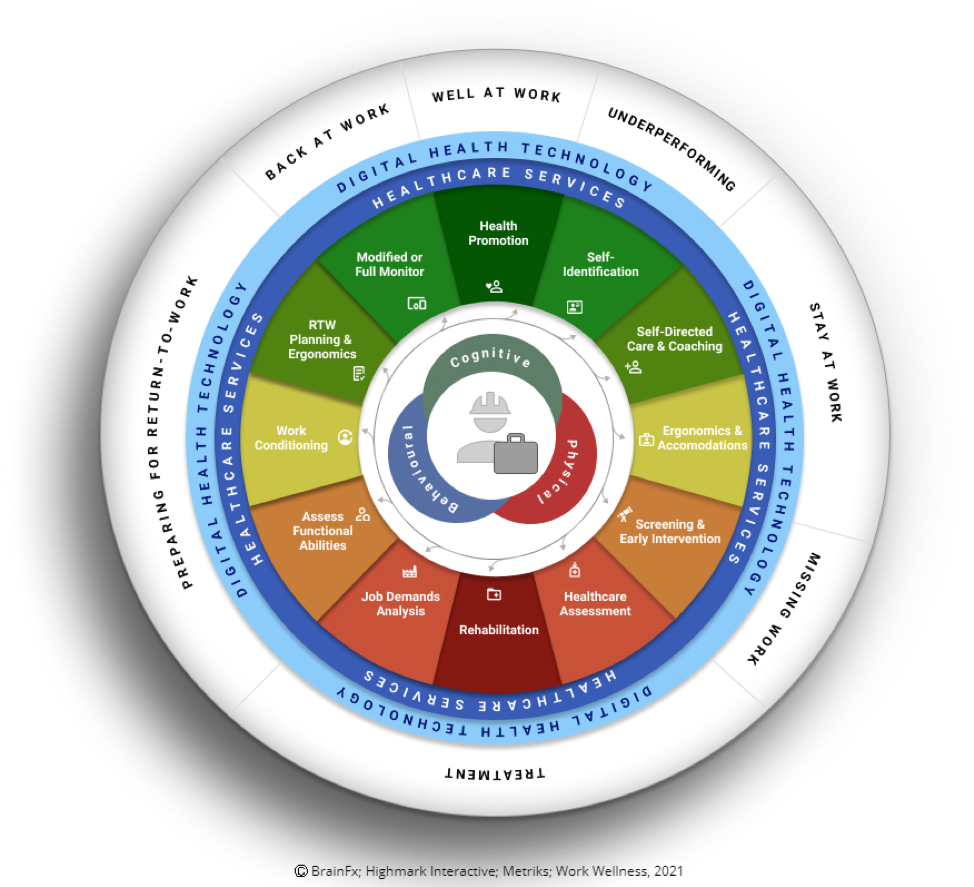

As is illustrated in Fig. 1 below, cognitive health requires as much consideration in our evaluation and management of the workforce as do physical and psychological health. A whole-person approach can help enable employees and employers achieve that desired state of a fully engaged, highly functioning workplace of choice, where everyone achieves their potential for the benefit of the individual, the organization, and the broader community.

The challenge now for employers is how to achieve this higher level.

(Fig. 1)

What can employers do?

As with anything new the next question is where to begin?

There are many things employers can do to begin addressing cognitive health issues in the workplace whether it is from an individual or an organizational perspective.

We suggest the following:

Recognize

- that cognitive impairment can exhibit physically, behaviourally or in work performance; it’s not simply laziness

- that cognitive health is an important part of health, wellness, safety and productivity at work and integrate it as a consideration in all aspects of the business

- that cognitive factors must be included in policies and practices around employee well-being, health and safety, human resources, disability management, and benefits.

Analyze

- complete both physical and cognitive demands analyses of jobs

- require that your ergonomic and accommodation assessment include consideration of cognitive work demands

- use cognitive self-screens/assessments as early as possible for suspected mild-moderate cases of cognitive impairment to provide early intervention/prevention (changes in work performance)

- for disability and absence management use cognitive capacity evaluations to clearly identify challenges

- use cognitive screens and employee feedback to optimize performance potential when there are changes in the work or work environment (for example the introduction of a new software package).

Provide

- access and coverage for targeted treatments such as CBT, concussion protocols, and cognitive exercise provided by health professionals (R.Kin., PT, OT, psychologist, etcetera)

- health supports that address cognitive health in EFAP offerings

- wellness initiatives that include education on brain health and low-cost self-screening

- reasonable accommodation options for persons who may have cognitive challenges (i.e. noise distraction that impacts concentration, correct the environment to minimize the impact)

- health and safety measures to mitigate potential cognitive challenges — good signage, adequate lighting, removal of distraction in high-risk areas, etcetera.

In addition to these steps, the Wellness Wheel (Fig. 1) can be used to quickly help identify where we are and what assistance or services might need consideration.

Conclusion

There is a significant deficit in our understanding of cognitive demands and the role they play in building and maintaining productive healthy workplaces.

From basic performance issues to serious events such as accidents or major decisions that can significantly impact an organization’s operations, reputation, or success — the implications are major.

The good news is there is a great deal that organizations can do to better assess and manage cognitive challenges. There are opportunities to leverage existing, validated tools, resources and methods across all facets of the work journey.

COVID-19 has heightened the sense of urgency many organizations have to ensure they not only retain their employees, but also enable them to deliver optimal performance in a challenging time.

Conny Glenn, R. Kin., is the president of Work Wellness in Kingston, Ont. Allan Smofsky is a workplace health strategist at Smofsky Strategic Planning in Toronto. Rensia Melles is a workplace mental health consultant at Integral Workplace Health in Toronto.