Climate change brings the heat

By Treena Hein

Rising temperature puts safety of outdoor workers in spotlight

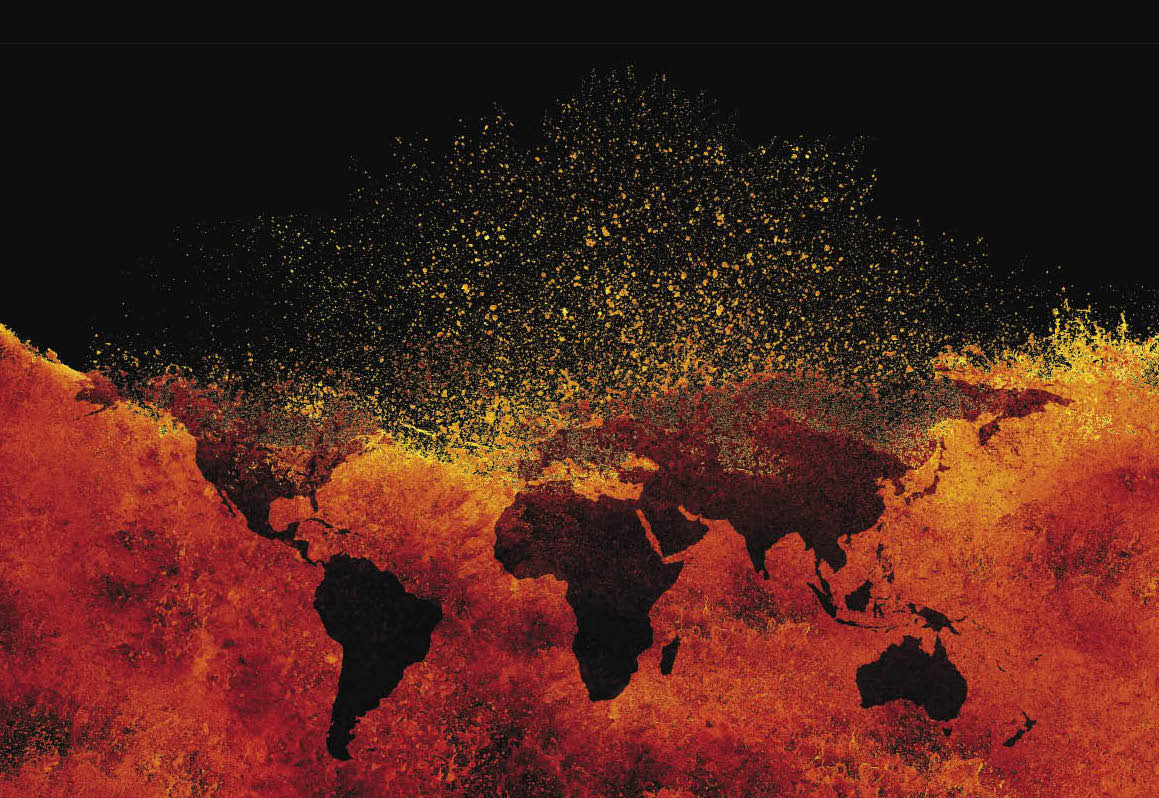

A new ILO study indicates heat stress will have a major effect on workers across the globe over the next 10 years. (ImagedPotPro/Getty Images)

Awareness of the impacts of climate change has perhaps never been higher in Canada.

It was a central focus in the recent federal election, and dealing with the fallout is something that all OHS professionals need to think about and plan for.

Not only are average temperatures rising globally, but more temperature variability is expected going forward, according to Chris McLeod, associate professor at the University of British Columbia and co-director at the Partnership for Work, Health and Safety in Vancouver.

“We’re going to have more extreme weather events, as well as more extreme hot days and extreme cold days.”

A recent study by the United Nations’ International Labour Organization (ILO) in Geneva, Switzerland, indicates heat stress will have a major effect on workers in the next decade.

A rise of 1.5 C by the end of century may result in a drop of 2.2 per cent in working hours across the world — equivalent to 80 million full-time jobs, according to Working on a Warmer Planet.

Heat stress is an important consideration for worker well-being and business profitability, says Catherine Saget, ILO research chief. When workers are not functioning at normal capacity due to heat stress or other factors, productivity is lower, injuries can occur and equipment damage can result.

“At 26 to 27 C, workers start to slow down,” she says. “At 35 C, worker speed is halved.”

Outdoor work is the most significant concern, as is work in certain sectors where warm conditions are already the norm, such as kitchens, factories and mines, says Saget.

But heat stress can also be present in office environments during a heat wave, she says, noting cities are more likely to have conditions that cause heat stress, with temperatures that can be up to eight degrees higher than surrounding areas.

Warmer air temperatures could also equal rising air pollution levels, according to McLeod.

And as people become more heat stressed, their response to poor air quality may degrade, he says.

“Some may need to be accommodated more than others and given different responsibilities. Age would be one factor, but also body weight and whether or not the worker has a chronic condition.”

Prevention, accommodation

There is a broad range of mitigations that OHS professionals can take to address heat stress, says Saget.

“Employers should provide adequate water, allow workers to work at their own pace and also train everyone to recognize signs of heat stress in themselves and others,” she says.

“They could also make space for dialogue with workers to reach consensus on how to adapt working hours, dress codes, break times, equipment usage and — especially in the construction sectors, with potentially high levels of illegal, migrant and non-organized labour — it is very important to have physical signs and all other aspects of awareness campaigns in the appropriate languages.”

All possible prevention and accommodation options should be assembled in a central heat-exposure control plan, and OHS professionals need to ensure they are trained in when to engage the plan, says McLeod.

Implementing the plan should include a morning meeting — akin to the daily safety meeting that’s held in many workplaces, he says.

“It’s important to be proactive and remind people of things at the beginning of the shift. Go over the plan and how everyone should engage the plan. Maybe there should be supervised hydration, or a place for workers to cool off, and maybe not just water, but water with electrolytes should be available.”

Further strategy could include checking the weather forecast, but also having reliable monitoring systems of the worksite environment in place, according to Saget.

Humidity levels, breeze and other factors all affect how much heat is experienced by humans — and some factors may not be very apparent. For example, because hats reduce the amount of heat that is shed from the head, some experts suggest that workers in direct sunlight should swap their hats for visors.

Jean-François Larochelle rides a stationary bike in a laboratory at Laurentian University in Sudbury, Ont., under the watchful eye of student Daniel Clark, middle, and Dominique Gagnon. The group is studying ways to prevent the depletion of bodily sugars during physical work. (Photo courtesy of CROSH)

When people are exposed to hot environments, they burn more sugars, according to Dominique Gagnon, researcher at the Centre for Research in Occupational Safety and Health (CROSH) at Laurentian University in Sudbury.

“Since we store limited stores of sugars, prolonged work in the heat leads to depletion of sugars and fatigue,” he says. “Unless someone working in the heat remains hydrated and ingests small but constant doses of sugars, there is a high likelihood that fatigue will occur, compromising safety, productivity and ultimately health.”

This is where a buddy system can work very well, where workers remind each other to drink enough water and sugars, or to take breaks as mandated in the plan.

However, it’s important to remember that a buddy system is only a part of what an organizational commitment to safety should entail, says McLeod, noting workers may not necessarily be in close proximity to their colleagues throughout a workday.

Having an awareness of collective responsibility, educating workers on signs of heat stress and individuals taking action are each important, he says.

“But we all have to realize that in some circumstances, there must be limits on how much workers are asked to do on a hot day and how long they should work. It doesn’t have to be that hot for these limits to be appropriate.”

Hands-on tools

Some helpful options are already available for OHS professionals in the climate-change fight.

Led by Dr. Ariane Adam-Poupart, the Institut national de santé publique du Québec (INSPQ) is working to strengthen the capacity of workplace adaptation to the impacts of climate change.

The first conceptual framework of the potential impacts of climate change on OHS in Canada, with a focus on Quebec, was published by Adam-Poupart.

In this framework, five types of hazards that could have direct or indirect impacts on workers were identified — heat waves, air pollutants, ultraviolet radiation, extreme weather events and zoonotic diseases.

The framework also includes research on the negative psychosocial impacts on workers of extreme weather events such as floods, workplace risks associated with zoonoses such as Lyme disease and West Nile virus, as well as adaptation measures to protect workers.

Specific tools include pamphlets for workers and employers regarding Lyme disease — available in a variety of languages — and a related interactive training tool, currently available only in French.

Other bilingual tools include guidelines for OHS professionals to calculate break times in heat waves and a worker survey form to guide the creation of a heat-wave report.

Novel technologies are also likely to be introduced in a variety of occupations to deal with heat stress, says Gagnon, and many have already been developed for workers in Canadian mines, including cooling garments, gear and temporary cooling rooms.

Treena Hein is a freelance reporter in Ottawa.