Teacher burnout a worry amid new-look safety protocols

November 23, 2020

By

OHS Canada

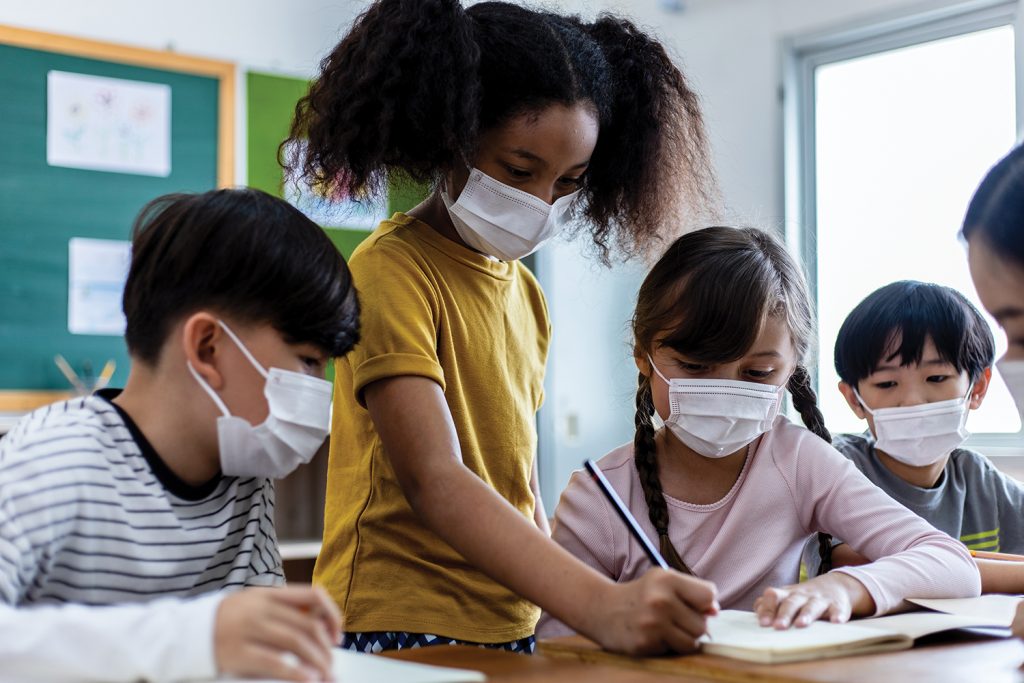

Across Canada, classrooms have been transformed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, in an academic year unlike any others

Teachers across Canada have seen their classrooms transformed this year due to physical distancing measures implemented due to the COVID-19 pandemic. (Vladimir Vladimirov/E+/Getty Images)

By Pierre Chauvin

At the end of August, teachers across Canada were preparing for a year like no other.

“Our hearts were breaking,” said Robyn Gasparini, a kindergarten teacher in Mississauga, Ont.

With 29 years of experience behind her, fall’s return to school started with a difficult task for Gasparini — undoing years of work put in to make her classroom welcoming to her students.

Carpets, little couches, cozy furniture: everything had to go.

“Everything that we’ve done to make our spaces welcoming and comfortable — a place where you feel like you belong — all of a sudden were very sterile,” she said.

New health guidelines to reduce the risks of COVID-19 transmission meant that many activities requiring sharing games and space were no longer possible.

By her own account, half of Gasparini’s teaching time is now spent completing cleaning tasks.

While her junior kindergarten students got used to the new routine, it wasn’t the same for senior kindergarten children who had experienced a “normal year” in 2019.

“’Miss Gasparini, do you remember when we used to be able to sit on the carpet and hold hands?’” Gasparini recounts children asking her.

Her voice breaks.

“It’s really hard right now,” she said. “The hardest part is not letting the kids see how hard it is on us.”

Pandemic rules

Across the country, provinces and territories have rolled out various back-to-school models playing on similar variations — a combination of in-class and remote learning.

But it’s not just the cleaning and technical requirements that are putting pressure on teaching staff. For many, it’s having to adapt an entire curriculum to new teaching realities that don’t allow for much of the student-led model.

“There’s a lot of co-operative work between students, as teachers guide processes and make tools available and provide instruction where it’s needed,” said Elizabeth Mitchell, who works for the Halton Elementary Teachers Local in Ontario, referring to the pre-pandemic model.

Her local is part of the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario, which represents 83,000 teachers across the province.

“That kind of teaching is absolutely impossible in this virtual classroom environment,” according to Mitchell.

In Ontario, teachers had two to three professional development days to get acquainted with the new model. But as Mitchell puts it, a few days aren’t enough to learn “a brand-new job.”

The logistics involved require the teachers’ constant attention.

Maria Marcello, a Grade 2/3 teacher in Woodbridge, Ont., juggles between two to three computers — one projecting on an interactive board for her in-class Grade 3, one for the Google Meet for her Grade 2 students, and a third one to share the screen of what Grade 2 is working on.

But even when everything runs smoothly on the technical side, it’s still a struggle to recreate the in-class experience with many students turning their cameras off, she said.

“I can’t gauge their understanding of anything that I’m teaching, and then I also lose that connection with my remote learners because I miss the cues of their body language,” said Marcello.

For other students, the process of unmuting themselves and speaking in front of the entire virtual class, with everybody explicitly listening to them, seems to bring as much apprehension as a class presentation.

“If we ask questions and they don’t respond, we don’t have any follow-up; we can’t get a hold of them because they’re not there, they’re not in front of us,” said Michael Kearns, a Grade 11/12 teacher in Cambridge, Ont.

Remote learning brings in other sets of unexpected challenges — more sources of distractions for students sitting in front of a computer, and for younger students, the occasional parent intervention to troubleshoot technical issues.

Burnout worries

Managing new safety protocols alongside regular duties has many teachers expressing burnout worries. (JR-50/Adobe Stock)

With the added responsibility of keeping their students safe, the classroom clean, and running a new model of teaching, many teachers in Ontario point out it will be impossible to complete the curriculum.

“How effective can we be before burning out?” Marcello asked. “On top of teaching, we’re doing so much more.”

A variety of interviews reveal the same trend — teachers are exhausted, mentally and physically, and don’t feel protected.

In late October, the Canadian Teacher Federation (CTF) launched a survey asking teachers about their mental health and well-being.

Of the 13,777 who responded, 46 per cent reported concerns about their own mental health and well-being. Compared to the same set of questions asked in June, the situation appears to be deteriorating quickly.

“These comparative results show a significant and negative change in teachers’ feelings of well-being,” the survey reads.

Physical health and safety ranked fourth in teachers’ overall concerns for their well-being, behind mental and emotional exhaustion; workload and work-life balance; and stress, anxiety and depression.

Marcello told OHS Canada of “teachers in tears,” while Gasparini says she forces herself to put on “a happy face” for her kindergarten students.

Evaluating safety protocols

In British Columbia, a recent survey found that the majority of teachers regarded health and safety protocols to be inadequate or completely inadequate.

B.C. Teacher Federation (BCTF) president Teri Mooring said a mask mandate and a reduction in class sizes are two measures many are asking for.

The levels of exhaustion witnessed across the country among teachers is unusual for this early in the school year, CTF president Shelley Morse noted.

“The people who have the power to change these situations need to step up and support our teachers, or we’re going to have a shortage of teachers because of ailments,” she said.

PPE is now required in many classrooms across the country. (Miodrag Ignjatovic/E+/Getty Images)

While the CTF calls on governments to take measures regarding staffing and teachers’ well-being, it’s interesting to note it’s also asking for unified safety guidelines within provinces and territories.

In Ontario, Mitchell points to a Toronto District School Board proposal to shorten teaching days in order to cap classes at 15 students in an effort to respect health guidelines.

“The (Ontario) Ministry of Education just threw the proposal out,” Mitchell said.

OHS Canada requested an interview with Ontario’s Ministry of Education.

Instead, it received a statement listing the additional money provided to school boards and detailing the measures developed with the chief medical officer of health.

“School boards are permitted to adopt adaptations that support smaller class sizes, more physical distancing and other health and safety measures, provided they meet certain parameters,” the statement reads.

The Halton District School Board did not reply to multiple requests for comment.

In some schools in Ontario, “teacher zones” have been implemented to allow for physical distancing. But as Mitchell learned when a concerned teacher reached out to her, those zones can’t always be used.

“The best they could do for that teacher’s ‘teacher zone’ would be for her to stand in the very corner of the classroom and teach from there,” she said.

“She couldn’t access the board, she couldn’t access the projector, she couldn’t even pull a cart with a small whiteboard and chart paper… but that was the place that she was supposed to teach in order to stay safe.”

In B.C., Mooring points to the lack of enforcement mechanisms to make sure school boards follow safety guidelines.

“We haven’t really seen WorkSafeBC playing an active role in enforcing those guidelines under a COVID scenario,” she said.

“Some districts are questioning whether the Ministry of Education guidelines are actually enforceable and, of course, that hasn’t been tested.”

And while the BCTF could file a grievance, that process would take up to six months, a timeline not feasible when a lapse in safety measures during a few hours could cause a COVID-19 outbreak.

Still, the BCTF says they’ve been working with the government to find a solution.

In a statement provided to OHS Canada, B.C.’s education ministry noted that “all boards of education and independent school authorities are required to implement strict health and safety guidelines” to deal with the pandemic.

Pressure on school boards

The pressure the pandemic brought on the education system is also felt at the school board level.

Since March, school boards have had to deal with unprecedented logistical challenges.

In B.C., the Francophone school board’s students and staff use over 8,000 laptops and tablets. Another 1,400 had to be ordered, all of which have to be properly set up by the IT staff, on top of bandwidth issues.

“That… has been let’s say, a kind of success because the IT people did work like crazy,” according to Michel St-Amant, head of the B.C. Francophone School Board.

But that’s not the only department that had to field a never-ending workload. Communications, he said, “has been working at 200 miles per hour.”

With anxiety running high and parents hearing from different sources, St-Amant said his team has had to debunk a number of false stories.

In one case, the school board was falsely accused of a lack of transparency.

Because of confidentiality rules, a school board will know about a case from public health, but won’t be able to disclose it unless it’s already been disclosed by public health.

But nothing prevents individuals from disclosing they’ve tested positive — creating a false impression of secrecy, St-Amant said.

“We don’t know what we don’t know — no one went through that kind of thing before,” he said.

Even with his experience working in Ontario during the H1N1 pandemic of 2009, the current COVID-19 is completely new territory.

And, of course, there are the COVID-19 cases. When interviewed in early November, the Francophone school board executive director told OHS Canada seven of the 45 schools were dealing with cases.

In Ontario, there have been more than 2,600 COVID-19 cases in schools through the first two months of the school year.

With the second wave in full force across the country, the situation seems more and more untenable.

Pierre Chauvin is a freelance writer in Victoria, B.C.