Elevated risk: Vertical transportation amidst COVID-19

September 2, 2020

By

OHS Canada

Coronavirus has made high-rise buildings difficult to navigate safely

Physical distancing and avoiding touching surfaces is more difficult in an elevator. (New Africa/Adobe Stock)

By Peter Saunders

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently shared a research letter, previewing an article to be published in the September 2020 edition of its Emerging Infectious Diseases (EID) Journal, describing how a single, asymptomatic carrier of COVID-19 generated a cluster of at least 71 cases after returning from the U.S. to China’s Heilongjiang province in the spring.

Referred to as ‘case-patient A0,’ she self-quarantined at home. It is believed her downstairs neighbour, case-patient B1.1, was infected via contact with surfaces in their apartment building’s elevator, which they had used at different times.

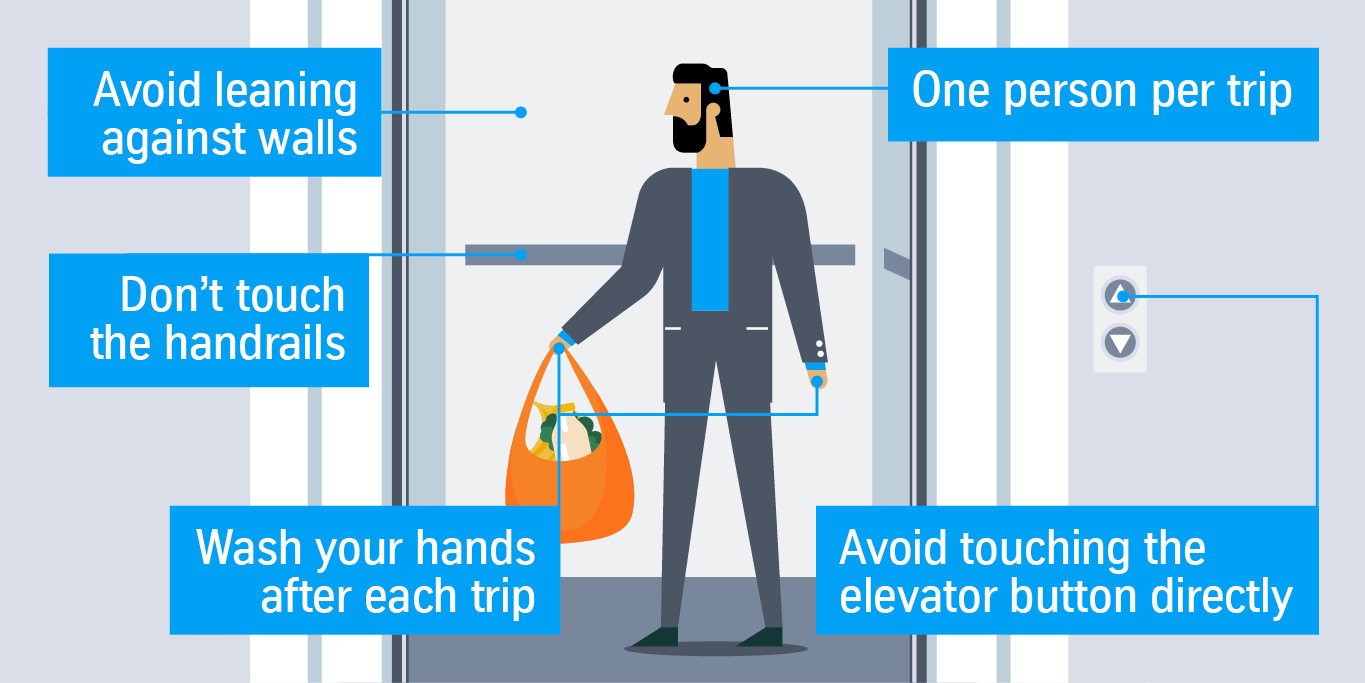

The study highlights the risk of elevators as contagion vectors. While occupants can easily wear masks, distancing from each other and avoiding touching surfaces are much more difficult in the normal context of vertical transportation.

“We can design elevators to carry only two people per trip, but then you’re going to need a lot more of them in a high-rise building,” says Jonathan Soberman, P.Eng, who runs a Toronto-based vertical transportation consulting firm, Soberman Engineering.

“Fewer people have been going into office buildings, but in residential high-rises, they have no choice but take the risk.”

In terms of preventing infection via surfaces, options include oversized foot-pedal buttons, which one of his clients has placed in an elevator for a mid-rise university residence — while in taller buildings, card readers and smartphone apps can call elevators and direct them to an individual’s chosen floor.

“You can also have people press buttons with their elbows or specify naturally antimicrobial copper buttons,” he says.

As for airborne particles, he says air-conditioning systems and higher-capacity exhaust for elevators could help.

“There are exhaust fans at the tops and vents on the floors, but there could be more of them,” he says. “The biggest exchange of air is when the doors open. The best approach would be combining the air handling system with high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filtration.”

Andrew Wells, senior vice-president (SVP) of Toronto-based KJA Consultants, used to work for Soberman and has similarly tackled the question of how elevators can be made safer during the global pandemic. As he puts it, ‘best practice’ recommendations are subject to change as we learn more about the virus.

“Masking and distancing mitigate risk,” he says. “I understand that in Asia, Salesforce has introduced a ticket-booking system for elevators in its buildings. In cities like Toronto, tenants in residential high-rise buildings could do that too to stagger use, giving priority to immunocompromised people.”

Wells has also researched disinfection by UV-C light. This type of lamp is used for sterilization in health-care and food-production facilities, as its radiation damages viruses’ genetic material sufficiently to leave them inactive. It can also hurt people, so it is only used in isolation from them, but Wells spies such opportunities even for busy elevators.

“Working within the recommended guidelines, I’ve seen a ventilation fan at the top of the elevator incorporating a contained UV-C bulb to sterilize the air passing through it,” he says. “In addition, as buildings are getting cleaned more frequently, so are their elevators’ surfaces.”

As for avoiding pressing buttons, he adds, “the technology is coming where proximity sensors will mean you don’t have to,” citing the security-driven example of One World Trade Center in New York, where swiping a card at a turnstile books a call and assigns an elevator to take the carrier to their destination.

“There will be long-term, significant changes,” says Wells. “Society can capitalize on lessons learned during this pandemic.”

Manufacturers have already responded. Thyssenkrupp Elevator, for one, launched a task force at the onset of the pandemic to consider both physical and digital technological measures.

On the physical side, the company has looked at handrail sanitizers, no-touch buttons (including the aforementioned foot pedals), HEPA filtration with UV air disinfection and even lamps that could operate overnight to disinfect the entire elevator cabin.

“There have been massive numbers of requests from our clients to adjust controls for our new and existing elevators to help their tenants get back to work,” explains Jon Clarine, head of digital services.

“Many of these changes are digital, such as programming elevators to only load a certain number of people or support remote smartphone calls based on proximity and identification. We’ve updated our software for hundreds of buildings applying these changes.”

There is also the issue of maintenance, which should not be deferred is possible, but has been difficult for emptied buildings.

“We also launched our Internet of Things (IoT) platform, Max, in 2015,” says Clarine, “It connects elevators through the cloud and lets our customers manage maintenance remotely, meaning fewer people have to go into the building.”

Otis, another manufacturer, has seen a similar increase in interest from building managers and developers in technologies that can address concerns raised by COVID-19. On the physical side, the company’s elevator purification fan can use either an anion generator (i.e. air ionizer, which produces negative ions) to reduce airborne transmission or the aforementioned UV-C lamp to inactivate viruses.

On the digital side, Otis’ Compass destination dispatching system can limit the number of passengers assigned to an elevator cab, while its eCall app allows smartphone users to remotely call and direct their elevator to where they want to go.

And like Thyssenkrupp, Otis offers an IoT service, dubbed ‘One,’ which along with remote monitoring is intended to improve elevator uptime and limit physical, on-site service visits.

“Trends we’ve seen among building owners are to work with tenants to stagger passenger arrival and departure times, install temperature checkpoints, use social distancing floor markers, limit elevator occupancy and install hand sanitizer stations through common areas of the building,” says Jordy McMillan, director of sales for Otis Canada.

“We see COVID-19 accelerating demand for current digital technologies to promote social distancing. IoT, predictive maintenance, destination dispatching, touch-less, keycard readers and in-car communications are all relatively new developments that may become more common.”

Peter Saunders is the editor of Canadian Consulting Engineer, a sister publication to OHS Canada.